A Dinner at Sea

An essay by Dr F W Boreham, O.B.E. He kept a copy of this essay in his writing desk. It was published in the Victorian Baptist Witness on September 5th, 1956.

It was at Bombay that I caught my first glimpse of the gorgeous magnificence of the East. And, in leaving India, a thing happened that struck me as intensely significant.

We were on a P & O liner – the ‘Maloja’ – bound from Sydney to London. Sailing along the Australian coast, and for the first day or two after leaving Fremantle, everybody wore lounge, suits and sports costumes on deck, and at the midday meal but when the dressing-gong sounded, its warning of the approach of dinner, we all retired to our cabins, and, when the bugle called half an hour later, we reappeared in evening dress. In the sumptuous saloon, softly and tastefully illuminated, the spectacle was a particularly pleasing one, and the meal, with its attendant preparations, and subsequent adjournment to the lounge for coffee and gossip, constituted itself the outstanding event of the day.

Then we plunged into the tropics. Three factors modified our previous programme. (1) The heat, becoming increasingly oppressive, our retire was reduced to a minimum. (2) We became more and more familiar with each other, and less and less inclined to stand on ceremony. And (3), the deck sports becoming more absorbing, the dressing-gong was in many cases, simply ignored.

As a consequence, the saloon at dinner time looked every night, a little less imposing. Men appeared in flannels and blazers. Some in shirts open at the neck, presented themselves, without either collars or ties. Women wearing their hats as at lunch, and garbed in the jumpers and tennis frocks in which they had disported themselves in the games on deck, thought, no more of the lovely gowns that they had displayed with such pardonable pride in the earlier days of the voyage. Every evening the saloon looked more disreputable. Dinner degenerated into a mere matter of feeding; as a social and artistic event its glory had departed. By the time we reached Bombay, we had fallen as low as it was possible to fall. We remain decent; that was all.

On arrival at Bombay, it was whispered among us that the places of those who had disembarked at Ceylon were to be filled by a large contingent of army officers and their wives, who were leaving India for England on furlough. As soon as we had sailed, the newcomers appeared on deck – the men in khaki shorts; the women dressed very much as our women were. In due course, the dressing-gong sounded. Nobody notice that, almost instantly, the officers and their ladies quietly vanished from the deck. Thirty minutes later, the bugle rang out. There was a general stampede for the cabins; everybody indulged in a hurried toilet; and the tables quickly filled.

Then came the bolt from the blue. When, in all types of disarray, the three passengers were seated, the saloon door swung open, and in walked three handsome young officers, immaculately clad in evening dress! They were accompanied by their wives, who, attired in the most exquisite gowns, had silk shawls or delicately tinted scarves thrown lightly round their comely shoulders. Another group followed almost immediately – and then more – and still more!

The subdued and chastened atmosphere brooded over the entire company that evening. There was no general buzz of conversation; there were no boisterous shouts of laughter. Nothing was said about the dinner episode; but next evening, as soon as the dressing-gong sounded, the decks were as deserted as the decks of a derelict, and, at dinner, that night, the saloon would have done credit to the banqueting hall of a castle!

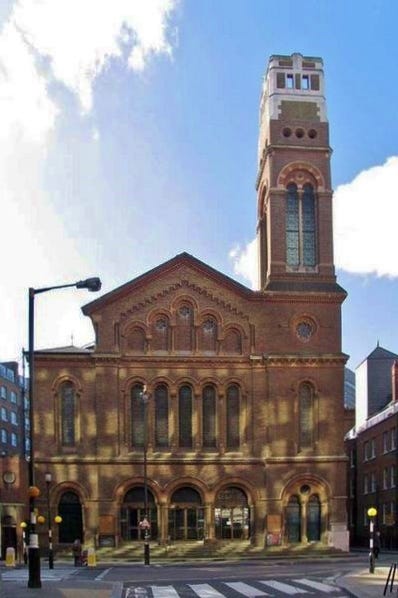

On a beautiful Sunday evening in mid-summer, I walked through Saint James’ Park, past Buckingham Palace to hear Dr John A Hutton at Westminster Chapel.

It was the only occasion in which I ever enjoyed that privilege. His text was, “I judge no man … but if I judge.” His point was that the general and gracious souls who would never dream of criticising us are the very people whose silent and unconscious condemnation is the most devastating.

A straight stick, lying besides a crooked one, does not judge its twisted neighbour, yet its very straightness, is the crooked stick’s most terrible exposure. Dr Hutton employed a homely, but singularly effective illustration. A man, sits grimly in a crowded tramcar, whilst a pretty girl stands near him, clutching at the strap. He mutters to himself that he has paid his fare, just as she has; that he is probably quite as tired as she is; and that he is in every way, entitled to his seat. She, of course, neither utters a word, nor casts a glance in his direction. Yet her very presence makes him thoroughly miserable and covers him with shame. “I judge no one… but if I judge.”

I never now think of Dr Hutton’s striking sermon, without recalling the transformation, silently effected by those British officers and their wives in the saloon of the ‘Maloja’. It seems to vindicate the contention of Francis of Assisi, who held that he who lives a beautiful Christian life has no need to resort to words in order to rebuke the iniquities that disfigure the Church and the world.